The Systems Behind Costumes on Canine Psychology: A Professional Analysis

- Oct 21, 2025

- 5 min read

Sparky Smith, MSST, ISCP.Dip.Canine.Prac., MCMA, SSBB

Systems Scientist | Architect of Canine Neurobiological Systems Science (CNSS) | Enterprise Transformation Strategist

ORCID iD: 0009-0006-8265-7488

As someone who has dedicated 30+ years to systems dynamics in both Fortune 500 environments and canine behavioral science, I've observed striking parallels in how causal loops affect complex systems across domains. My work developing the Canine Neurobiological Systems Science (CNSS) framework has revealed how seemingly simple interventions—like dog costumes—can create cascading effects through multiple feedback loops, particularly for dogs with trauma histories.

The recent online criticism I've received for this perspective only reinforces how essential this conversation is. When we apply systems thinking to canine welfare, we uncover insights that challenge conventional practices and align with emerging research in animal welfare science (1).

Systems-Based Analysis of Costume Impact

Drawing from systems thinking methodologies as applied to animal models (2), I've observed that the most significant breakdowns in canine welfare often stem from misunderstood feedback mechanisms. Contemporary animal welfare frameworks increasingly critique anthropocentric interventions with pets (3), providing empirical support for the systems-based approach I propose.

The causal loops created by costume use represent an illustrative case study in how multi-domain system dynamics operate in practice, with documented impacts on canine communication, autonomy, and stress responses (4).

Primary System Dynamics: The Misinterpretation Loop

When a dog is placed in a costume, we initiate a systems cascade with multiple reinforcing loops:

Costume Application → Dog Stress Response → Owner Misinterpretation

→ Continued/Reinforced Costume Use → Increased Dog Stress

→ Diminished Trust → Heightened Sensitivity to Future Interventions

This represents a classic reinforcing loop with compounding effects over time. Physical modifications, even mild ones like telemetry vests, have been shown to alter physiological parameters and behavior in canines (5), reinforcing the validity of this systems interpretation.

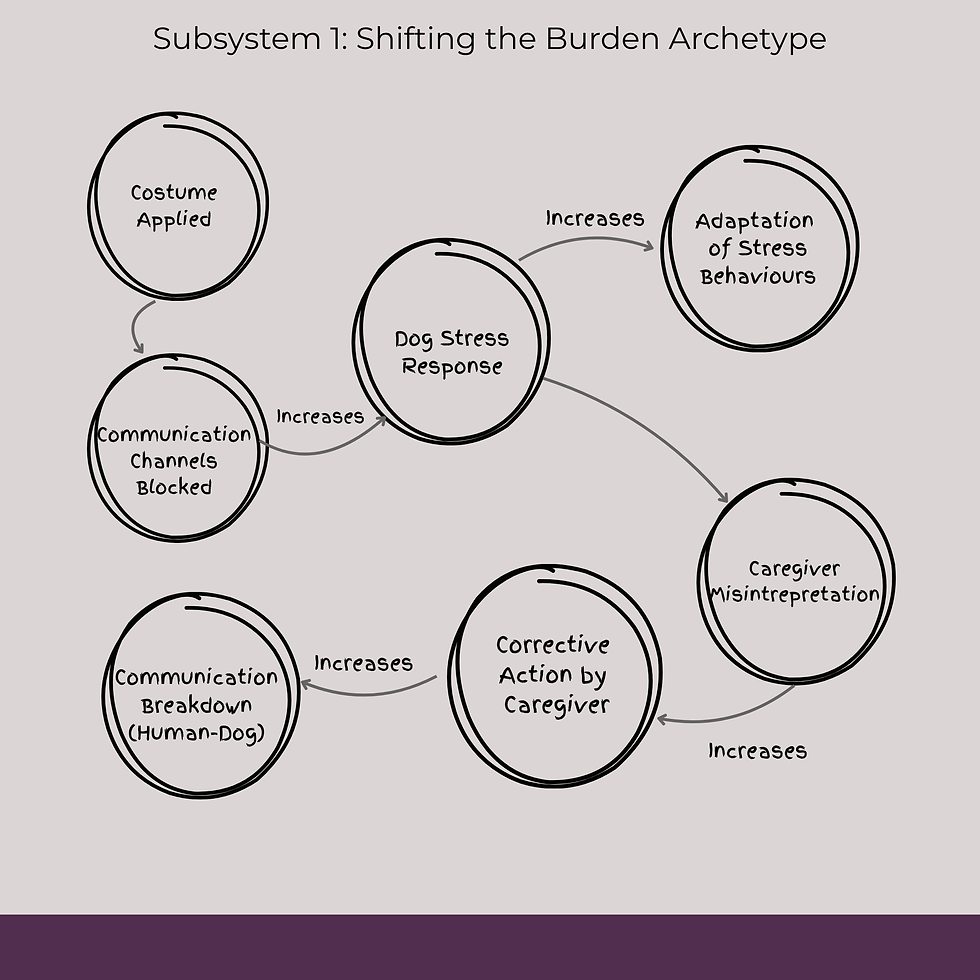

Subsystem 1: Communication Impairment Dynamics

The communication subsystem operates as follows:

Costume Blocks Communication Channels → Dog Cannot Signal Discomfort Effectively

→ Communication Signals Intensify → Misinterpreted as "Misbehavior"

→ Corrective Action by Owner → Further Communication Breakdown

→ System Adaptation Through Alternative Stress Behaviors

This represents what system dynamicists would recognize as a shifting-the-burden archetype. Multiple welfare organizations document that costumes can restrict canine communication signals, leading to anxiety, frustration, and misinterpretation by caregivers (6,7). The suppression of natural body language has been demonstrated to create significant communication barriers (8), consistent with clinical observations in behavioral practice.

Subsystem 2: Autonomy Regulation System

Through the CNSS lens, which integrates polyvagal theory (9), we can observe how autonomy violation creates another critical feedback loop:

Autonomy Violation → Neurobiological Stress Response

→ Sympathetic Nervous System Activation → Fight/Flight/Freeze Response

→ Owner Control/Restraint to Maintain Costume → Polyvagal Shutdown

→ Long-term Regulatory System Dysregulation

The polyvagal framework provides the physiological foundation for this autonomy regulation system (10), explaining how costume-induced stress can trigger defensive neurobiological responses. Translational applications of polyvagal theory to canine behavior (11) further support this model, demonstrating how interventions that compromise autonomy can fundamentally disrupt regulatory systems.

Subsystem 3: The Sensory-Social Feedback System

Perhaps the most insidious causal loop involves the interplay between sensory experience and social interpretation:

Costume Creates Uncomfortable Sensory Experience → Dog Becomes Distressed

→ Distressed Appearance Attracts Human Attention → Humans Display Behaviors

Interpreted as Threatening → Owner Fails to Intervene → Trust Breakdown

→ Defensive Response Activation → Response Constrained by Costume

→ Learned Helplessness → Regulatory System Collapse

Empirical learned helplessness research (12,13) supports the "regulatory collapse" concept; dogs exposed to uncontrollable stressors display behavioral resignation consistent with dysregulated autonomic systems. Environmental stressors, including auditory and visual stimuli (14), create similar patterns of response, reinforcing the sensory-social feedback model proposed.

Breaking Dysfunctional System Patterns

The CNSS framework suggests specific interventions to interrupt these maladaptive loops, drawing on established behavioral science while synthesizing multiple theoretical approaches:

Recognition and Response Realignment: Train caregivers to accurately read subtle canine stress signals and respond appropriately, creating a new virtuous feedback loop of trust-building.

Function-Over-Form Prioritization: When environmental protection is needed, select minimally invasive designs that preserve communicative capacity and autonomy.

Positive Association Building: For necessary interventions (medical clothing, anxiety wraps), implement systematic desensitization protocols that respect the dog's regulatory capacity.

Alternative Expression Channels: Redirect creative impulses toward options that don't compromise canine communication systems.

Individualized Assessment: Apply systems thinking to evaluate each dog's unique tolerance thresholds and history, respecting that system dynamics operate differently across individual canine neurobiological systems.

Conclusion: A Systems Transformation Approach

The CNSS framework extends beyond existing models by synthesizing polyvagal theory, learned helplessness research, and systems archetypes into an integrated approach specifically calibrated for canine behavioral systems. This synthesis allows for novel insights that individual models alone cannot provide.

The criticism I've received online for these views demonstrates how entrenched our anthropocentric approach to companion animals remains. Yet, when we apply rigorous systems thinking to canine welfare—treating behavior as an emergent property of dynamic, non-linear systems—we uncover insights that traditional single-domain perspectives miss.

By mapping the complex feedback loops between neurobiological subsystems, relational subsystems, and environmental subsystems, we can identify more ethical and effective ways to interact with our canine companions, consistent with contemporary welfare science (15).

True systems thinkers understand that resistance to paradigm shifts is itself a predictable system behavior—one that ultimately cannot prevent the evolution of better models.

References

1. Mota-Rojas D, Mariti C, Zdeinert A, Riggio G, Mora-Medina P, Del Mar Reyes A, et al. Anthropomorphism and Its Adverse Effects on the Distress and Welfare of Companion Animals. Animals (Basel). 2021 Nov 15;11(11):3263. doi: 10.3390/ani11113263. PMID: 34827996; PMCID: PMC8614365.

2. Mobus, G. E., & Kalton, M. C. (2015). Principles of Systems Science. Springer. [Relevant systems science textbook covering methodologies applicable to animal models].

3. Bradshaw, J. W. S. (2017). The Animals Among Us: How Pets Make Us Human. Penguin Books. [Critiques anthropomorphism in pet keeping].

4. FOUR PAWS UK. Halloween - Scary for pets too [Internet]. 2024 Oct 9 [cited 2025 Oct 21]. Available from: https://www.four-paws.org.uk/our-stories/publications-guides/halloween-scary-for-pets-too

5. Fish RE, Foster ML, Gruen ME, Sherman BL, Dorman DC. Effect of Wearing a Telemetry Jacket on Behavioral and Physiologic Parameters of Dogs in the Open-Field Test. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2017 Jul 1;56(4):382-389. PMID: 28724487; PMCID: PMC5517327.

6. What are the animal welfare issues with pets wearing costumes? [Internet]. RSPCA Australia [cited 2025 Oct 21]. Available from: https://kb.rspca.org.au/knowledge-base/what-are-the-animal-welfare-issues-with-pets-wearing-costumes/

7. ASPCA. (n.d.). Halloween Safety Tips. Retrieved October 21, 2025. [Provides general warnings about pet stress and costumes].

8. Siniscalchi, M., d'Ingeo, S., & Quaranta, A. (2021). The Dog's Body Language: A Guide for Interpreting Canine Communication. Animals, 11(7), 2024. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11072024 [Discusses how obstructing body parts can impair communication].

9. Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-regulation. W. W. Norton & Company. [The primary source for Polyvagal Theory].

10. Porges, S. W. (2007). The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology, 74(2), 116-143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.009 [Explains the physiological foundation of the autonomy regulation system].

11. Beerda, B., Schilder, M. B. H., van Hooff, J., & de Vries, H. W. (1997). Manifestations of chronic and acute stress in dogs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 52(3-4), 307-319. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1591(96)01131-8 [Documents physiological stress responses relevant to polyvagal concepts in dogs].

12. Seligman, M. E. P., & Maier, S. F. (1967). Failure to escape traumatic shock. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 74(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0024514 [The seminal learned helplessness study].

13. Maier, S. F., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2016). Learned helplessness at fifty: Insights from neuroscience. Psychological Review, 123(4), 349-367. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000033 [Modern review connecting learned helplessness to neurobiology].

14. Storengen, L. M., & Lingaas, F. (2015). Noise sensitivity in 17 dog breeds: Prevalence, breed risk and correlation with fear in other situations. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 171, 501-508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2015.08.020 [Example of environmental stressors creating dysregulated responses].

15. Mellor, D. J., Beausoleil, N. J., Littlewood, K. E., McLean, A. N., McGreevy, P. D., Jones, B., & Wilkins, C. (2020). The 2020 Five Domains Model: Including Human-Animal Interactions in Assessments of Animal Welfare. Animals, 10(10), 1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10101870 [Represents contemporary welfare science aligning with a systems-view].

#CanineNeurobiologicalSystemsScience #SystemDynamics #AnimalWelfare #CNSS #PolyvagalTheory #BehavioralSystems

Comments